Omenka Gallery is proud to present the second instalment of Networks and Voids: Modern Interpretations of Nigerian Hairstyles and Headdresses by celebrated Nigerian photographer, ‘Okhai Ojeikere and one of the fast-rising names on the continent, American artist, Gary Stephens who is based in Johannesburg. The exhibition is Omenka’s presentation at the already established, second edition of London’s global art fair, Art 14 London sponsored by Citi Private Bank. The inaugural edition of the fair in 2013 attracted 25,000 visitors, including 4,500 VIPs. The fair will take place from February 28 to March 2, 2014 at the Olympia Grand Hall in London.

Last October experienced the first instalment of Networks and Voids: Modern Interpretations of Nigerian Hairstyles and Headdresses at the Omenka Gallery, Lagos. It featured drawings, photography and prints, and was well received by art critics, collectors and connoisseurs alike.

This exhibition is next in a series of well-received and ambitious exhibitions organized by Omenka Gallery this year, to showcase some of the biggest names in contemporary African art, who though living and working outside the continent, remain true to their roots in their work. This initiative is part of Omenka’s increased participation in major international art fairs around the world including Art Dubai, UAE, the Joburg Art Fair, Cape Town Art Fair, Loop, Barcelona, Cologne Paper Art, Art14, and 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, both in London.

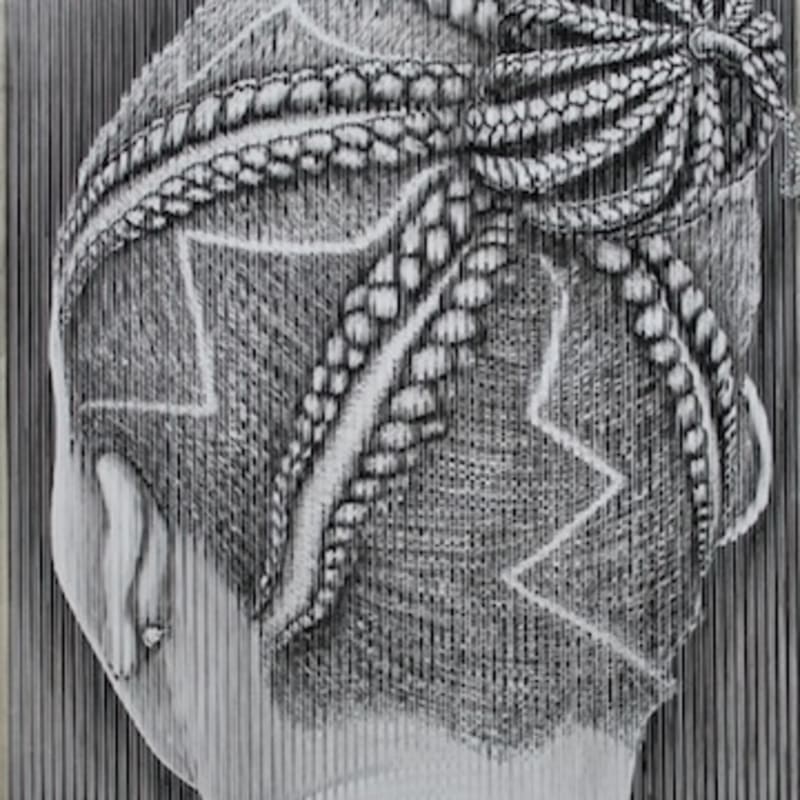

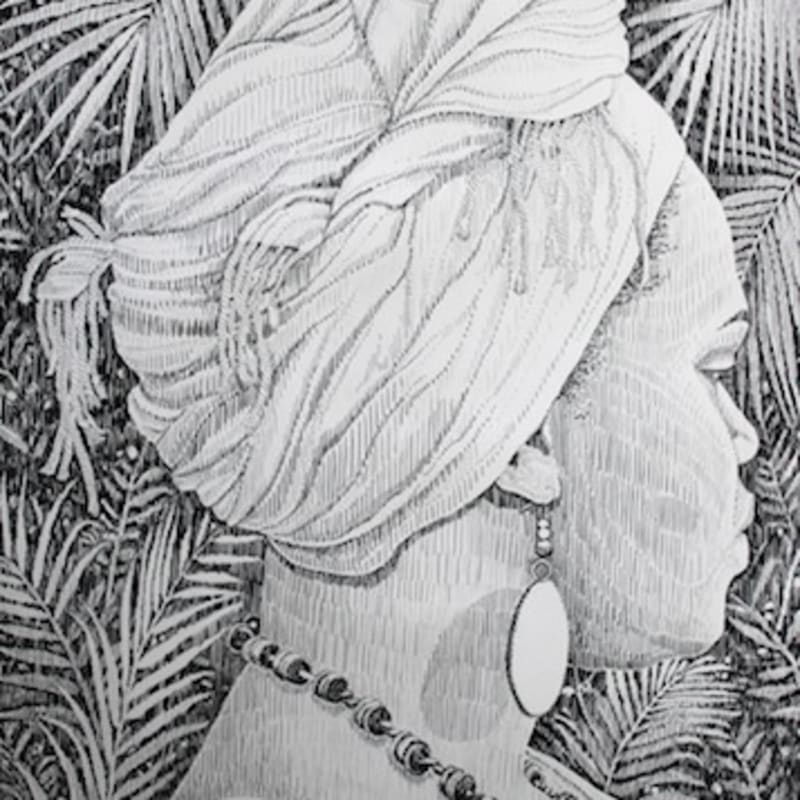

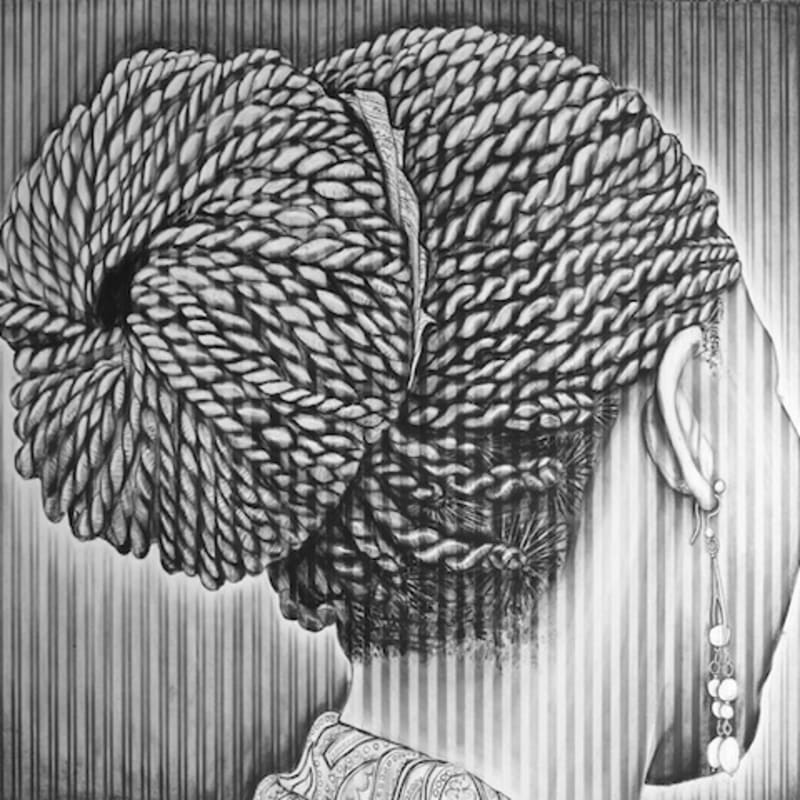

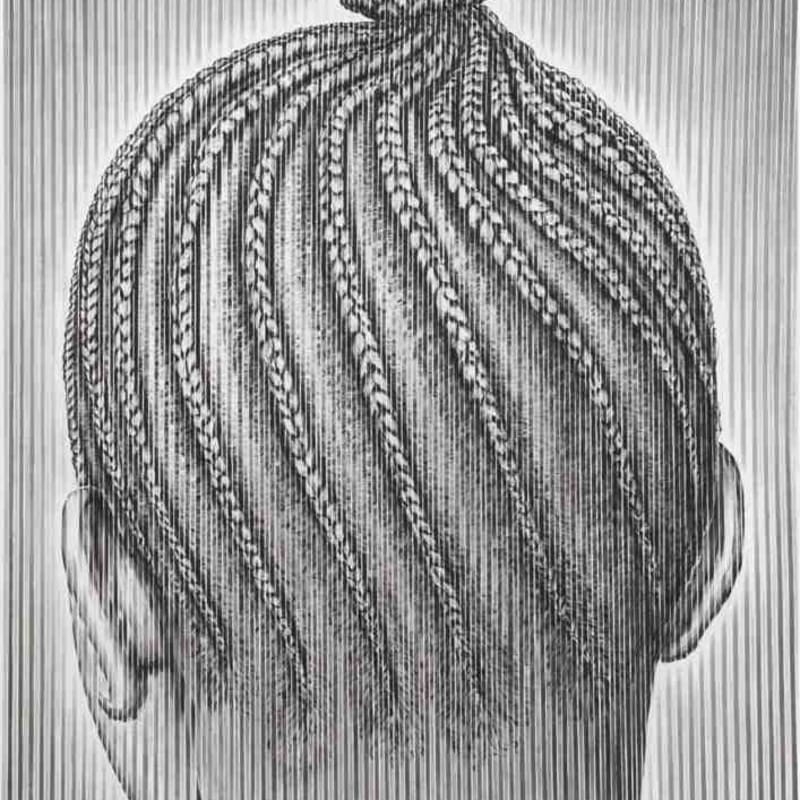

The works are presented in photography, linoleum prints and charcoal on paper, and are united by the central theme of Nigerian hairstyles and headdresses (geles) fashioned from hand-woven aso-oke and expensive imported textiles including damask, brocade and metallic-like jacquard. Both artists offer insight into Lagos society and successfully capture the creativity and opulence of social gatherings. The history of these fabrics is not only tied to the complex web of trade and negotiation between Africa and the West, but is related to Nigeria’s socio-political development during the oil boom. Today, the outfits produced from these luxurious fabrics are an expression of prosperity.

The show draws its title from the patterns formed by the network of interlocking branches of finely plaited hair and voids left in their wake. These patterns are repeated in the weaves of the headdresses, where they give the impression of low relief embroidery and mimic matching lace outfits populated by open spaces. This notion of interconnectedness is further accentuated by the fact that though the artists are separated along racial lines, location and age, they are brought together through the investigation of these art forms.

Historian, Elisha P. Renne asserts that by referring to some of these textiles as laces, Nigerian consumers emphasize the open perforations, thus making reference to a range of textiles (embroidered, painted, or cut) and body art practices (tattooing, cutting, and painting) that utilize a similar combination of textured designs placed in open spaces.

In traditional African society, hairstyles had immense religious and cultural significance. During the slave trade, hairstyles played a major part in communicating age, marital status, ethnic identity, religion, wealth, and rank. Young Wolof girls of Senegal partially shaved their heads as an outward symbol they were not courting. Igbo wives, on losing their husbands shaved off all their hair in mourning.

The study of black American history reveals that the slave trade inflicted physical damage as well as deep emotional and psychological scars, the most devastating, still reflected today is that done to the image. This is especially true as it relates to hair and skin colour, as parameters for determining race. The slave owners often described African hair as “wooly” and likened them to animals. These and several other terms were used to justify the inhumane treatment meted out to slaves. After years of repression and witnessing those with “straight hair” and “light skin” afforded better opportunities, the slaves began to internalize these words.

Against this background, works by Ojeikere and Stephens become veritable sites to assert the African identity and challenge these stereotypes. The works then assume greater importance and new meanings along two major lines of thoughts; first when viewed against the preponderance of imported human and synthetic hair and skin lightening beauty products, and second in documenting an ebbing culture. In modern times, the social significance and personal meaning of traditional hairstyles have been forgotten. Instead, ancient styles are re-born, with many variations linking them more with fashion.

At first glance, it seems rather disconcerting that the artists employ contemporary media and techniques to engage issues of preservation. Perhaps the similarities between the artists end here. In 1968, Ojeikere began to develop a series of photographs exploring Nigerian culture. The Hairstyles and Headdresses are his best-known and most significant bodies of work. Importantly, these series are shot in black-and-white and largely with an analogue camera, which lends to their cultural and historical significance. Time is at once frozen and the ephemeral nature of the hairstyles and headgears, which evolve with fashion trends, is preserved.

Also included in the presentation is a staged braid performance by Gary Stephens on March 1 in booth M28. The hour-long durational performance explores notions of beauty and examines the influence of modernity and the spread of globalization on post-colonial Africa. It involves 3-4 braiders continuously plaiting the hair of their models accompanied by a looped ambient soundscape. The artist calls this the Final Cut, and it consists of chatter between the braiders and their sitters typical of the streets of Johannesburg and Lagos.

Stephens has documented the topography of Johannesburg not as a visual sequence but as an interlocking series of rhythmic sounds affording the audience the opportunity of partaking in the performance by recognizing and identifying with the familiar that evoke memories while attempting to imagine the market banter and the impatient honking of motorists amongst several possibilities. Thus the work merges the cities with performance and sound in new and innovative ways, creating a dynamic moving installation.

Overall, the works are strongly individual, their juxtapositioning providing a sense of urgency to an immediate purpose – to challenge the various stereotypes thrust on the Africans.